A self-proclaimed pastime painter, Winston Churchill did not put brush to canvas until the age of 40. Although he received no formal training as an artist, he pursued his hobby with characteristic passion, and it became a lifelong interest.

the age of 40. Although he received no formal training as an artist, he pursued his hobby with characteristic passion, and it became a lifelong interest.

A 1920 essay, which later became the basis for his book Painting as a Pastime, serves as Churchill’s personal credo on the creative process and recounts the origins of his interest in painting. The essay describes how, in 1915, Churchill was pressured to resign his position as First Lord of the Admiralty following a disastrous campaign in the Battle of Gallipoli during World War I. "I had great anxiety and no means of relieving it," he wrote. With "long hours of unwonted leisure in which to contemplate the frightful unfolding of the war," he turned to painting as a means to clear his mind and relieve his stress — an antidote that served him throughout the remainder of his turbulent career.

The exhibition includes a total of seven original oil paintings by Winston Churchill, including the historically significant canvas, Firth of Forth, a recent gift to the Museum. The work was created circa 1925 in east Scotland, where the River Forth meets the North Sea.

Firth of Forth captures Churchill’s great knowledge of, and admiration for, the British  Royal Navy during a time of great change. The work depicts several Acasta-class British destroyers and other capital warships that Churchill knew well from his time as the First Lord of the Admiralty in World War I.

Royal Navy during a time of great change. The work depicts several Acasta-class British destroyers and other capital warships that Churchill knew well from his time as the First Lord of the Admiralty in World War I.

“While counterintuitive considering his reputation as a wartime leader, it was unusual for Churchill to paint military subjects, which makes this canvas quite rare,” explained Timothy Riley, the Museum’s Sandra L. and Monroe E. Trout Director and Chief Curator. “In the mid-1920s, when the painting was created, the World War I-era ships depicted in the painting were in the process of being decommissioned and scheduled to be sold for scrap. Churchill paints them steaming into harbor as the sun sets in the background, a poignant and almost melancholy scene, signaling the end of an era.”

Included in the exhibition are two newly installed Churchill paintings placed on extended loan: Leaning Palm, Jamaica, was painted in 1953 when Churchill visited the Caribbean island with his wife, Clementine, and the couple's youngest daughter, Mary, during his second term as Prime Minister.

extended loan: Leaning Palm, Jamaica, was painted in 1953 when Churchill visited the Caribbean island with his wife, Clementine, and the couple's youngest daughter, Mary, during his second term as Prime Minister.

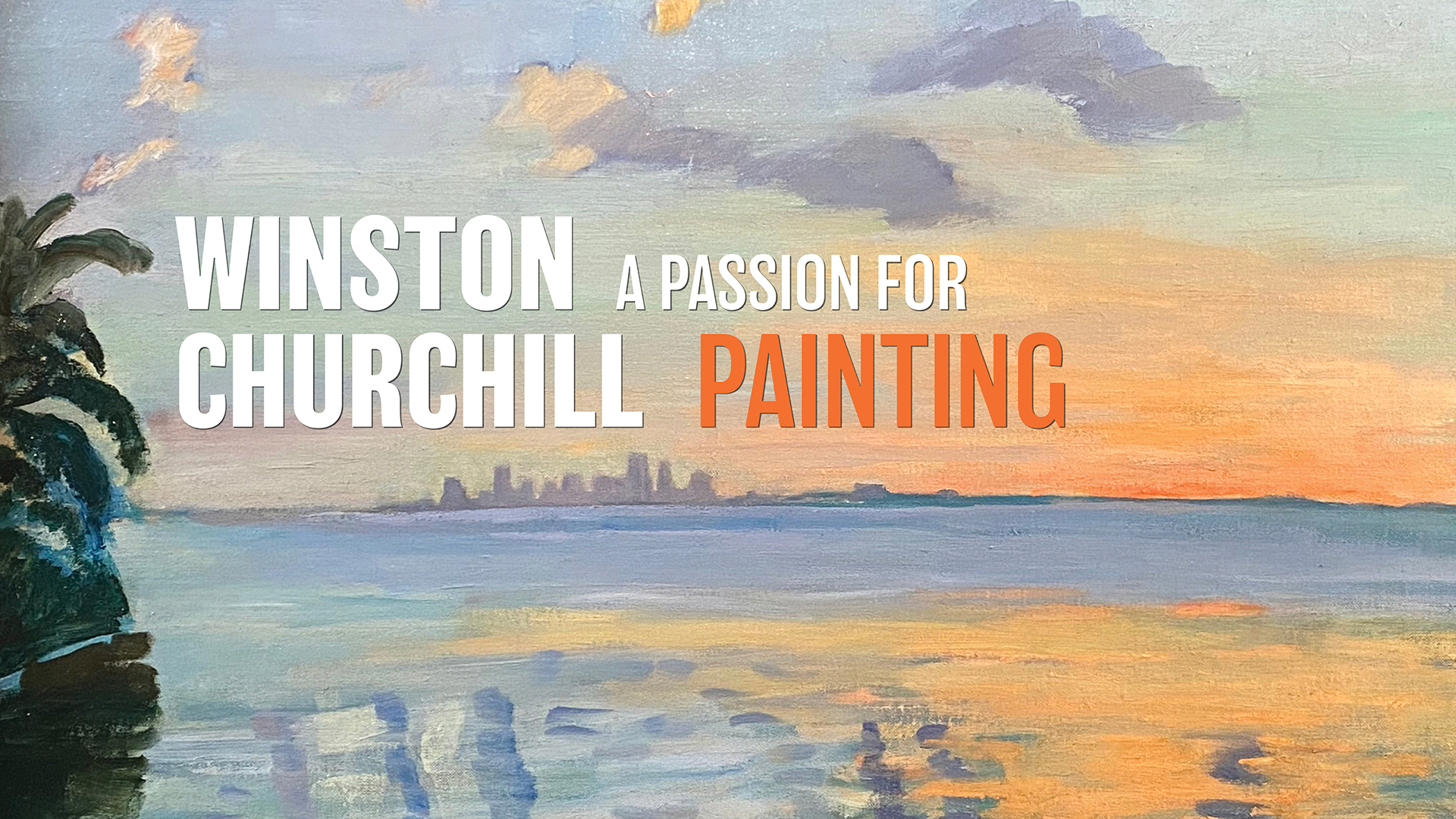

The other newly installed painting ― which since the 1960s has been titled "Distant View of Venice" and believed to be a view of the famous Italian city ― will be shown under a new title: A View of Miami at Sunset.

The painting received its new name after artist and Churchill researcher Paul Rafferty discovered the perspective of the tranquil scene infused with brilliant shades of cerulean and gold are actually of the Miami skyline painted from Miami Beach at sunset.

“A number of Churchill’s canvasses could be confused with Venice, Italy,” Rafferty  explained in an interview on Aug. 21. “Focusing my attention on the subtleties of this painting, I came to see 'Distant View of Venice' was actually the Miami skyline at sunset.”

explained in an interview on Aug. 21. “Focusing my attention on the subtleties of this painting, I came to see 'Distant View of Venice' was actually the Miami skyline at sunset.”

The September exhibition at ANCM will mark the first time the painting has been on view to the public since Rafferty’s discovery.

Churchill painted the seascape while visiting the Miami Beach home of Col. Frank W. Clarke at North Bay Road in Miami Beach in January and February of 1946, just weeks before the statesman traveled to Westminster College in Fulton, Missouri, to deliver his famous “Iron Curtain” speech on March 5, 1946.

“When viewed from across the street of Clarke's house, looking across Biscayne Bay, the actual location of the painting is revealed,” Rafferty said.

On August 10, America’s National Churchill Museum verified Rafferty’s findings and captured contemporary photographs and video from the exact site where Churchill created the canvas in 1946.

On August 10, America’s National Churchill Museum verified Rafferty’s findings and captured contemporary photographs and video from the exact site where Churchill created the canvas in 1946.

“Paul Rafferty’s discovery is remarkable,” Riley said. “It is incredible to imagine Churchill painting this beautiful scene of the sun setting over Miami while thinking about the danger of an iron curtain descending across the continent of Europe, a warning he famously issued here at Westminster College shortly after he painted this picture.

“Winston Churchill was indeed a visionary for all seasons … a keen observer not only of the immediate horizon, but also of everything beyond.”

Read the news release.

The exhibition is made possible, in part, by the Anson Cutts Fund and is in memory of Catherine Churchill, whose contributions to the study of Winston Churchill's paintings were great and many.

“Leave the past to history especially as I propose to write that history myself.”